Shape Up is written by Basecamp, the authors of Rework, Remote, It Doesn’t have to Be Crazy at Work, and Getting Real. Like many of their books, this one is very well done. It differs from some of their other books in that this is almost more like an autobiography. Like one would expect, it has clearly articulated descriptions of how they think work should be done, but this book is a deep dive into how they came to their internal process. Another unique thing is that Shape Up is free, but I would pay for it if it wasn’t.

Basecamp founders don’t seem to care much about common business practices, or what other people are doing. In fact, they sometimes seem to assume that everyone else is doing things wrong. They cleverly make fun of scrum, sprints, kanban, and others by saying that at Basecamp they aren’t “remotely tied to a metaphor that includes being tired and worn out at the end. No backlogs, no Kanban, no velocity tracking, none of that.”

The best parts

1) Appetite

The largest mind-shifting concept in the book is what they call “appetite.” They say, “Instead of asking how much time it will take to do some work, we ask: How much time do we want to spend? How much is this idea worth?” So it is the complete opposite of almost all Product team interactions I’ve had. I’m used to hearing something like, “How long with feature XYZ take?” but they flip it in reverse and say something like, “Can you complete XYZ in X time (6 weeks max)?”

How is this different, you ask? It ensures that planning, scoping, and thought were thorough enough to get a true benefit within a constrained amount of time. The time constraint is also a core concept. They offer a few edge case and exceptions, but for the most part they say that six weeks is the maximum time per iteration.

An appetite is completely different from an estimate. Estimates start with a design and end with a number. Appetites start with a number and end with a design.

— Shape Up

With this concept of appetite, they also don’t need to estimate. That is because Product limited the scope themselves and set the timeline.

2) Breadboarding and Fat Marker

The second best part is the concept of Breadboarding and Fat Marker. This is more focused at the Product team and the Design team. Breadboarding is basically a user-flow/data-flow diagram. This step is a simple text based diagram.

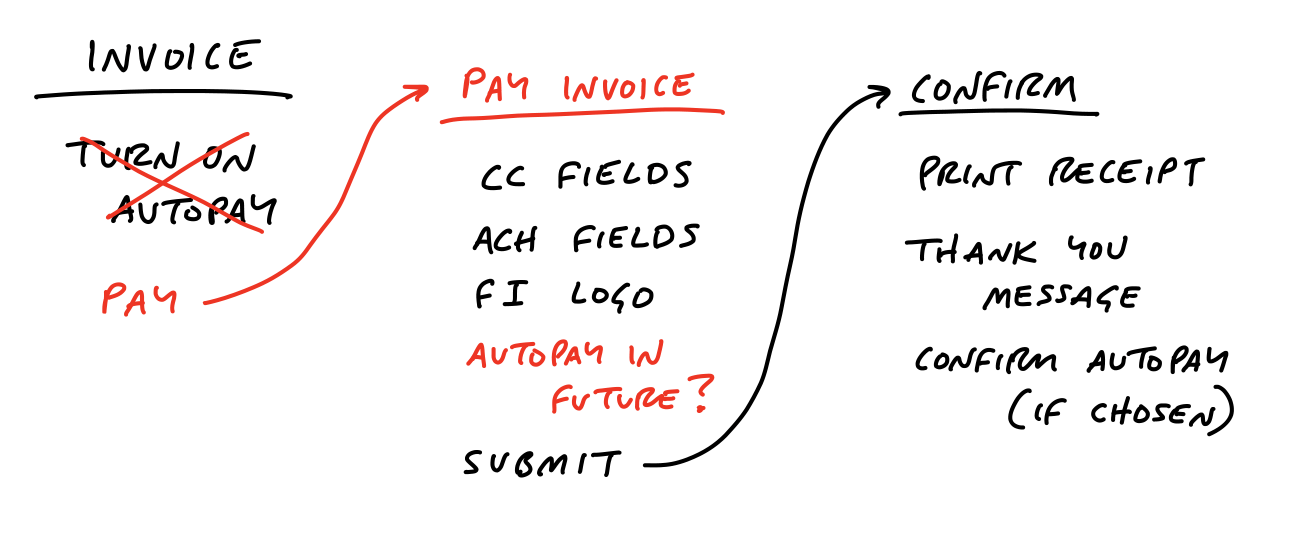

This example (from the book) shows that they discovered that there was a flow problem with the new idea and they fixed it. The reason this is important is that they were able to discover the problem way before wasting time with high fidelity mock-ups or user testing or even worse, dev time.

Next, they move to low-fidelity mockups. Some people would call it wireframe. To help define this, they call it “Fat Marker”. It must be completed with a larger, single color marker. The point is simply to show interaction within the page. There are a number of possible shortcomings that can be identified.

The Dangers

1) Culture confusion

First off, it is important to understand that they built their culture around this style. It is important to realize that process mimics culture, and not the other way around. Remember, this is their autobiography of their company.

You can’t simply mimic their process. The key is to take pieces of their process and adapt them in a way that fits your company culture.

2) Passive Aggressive Implementation

In my experience, the Product team often tries to do too much at once since someone gave them the “green light.” So my job has often been to be the bad guy and tell them to cut scope and move things to a future phase. Initially, I was excited to flip the pressure back on them, by telling them that they only had “X” weeks and they needed to get things scoped better. While this felt like a great burden off of me, it also is clearly an aggressive tactic that isn’t a team decision.

It is easy to think of the Product team as an adversary that pushes for ridiculous things or interrupts fun technical plans. This is not in the book at all, but seeing how they portray their plan as so amazing, it makes one think that they figured it out. In reality, this book should simply be used as a collection of ideas. In most situations, the concepts cannot be implemented with perfect carbon-copy from the book. One must enjoy this fresh approach, realize that these ideas are equally as successful as others, and pluck pieces of wisdom from the book to apply to one’s own organization.